The Feast of the Hunter’s Moon is coming up in a few short weeks – celebrating the fall gathering of the French and Indians at Fort Ouiatenon on the Wabash River, here in the 42nd’s hometown of Lafayette, Indiana.

The Feast features one of the most informative opening ceremonies of any living history event, using its 8 flag poles to cover the colonial history of the area, by relating it to the series of powers who controlled the Wabash Country.

While the 42nd Highland Regiment never visited Ouiatenon itself, the Regiment took an active part in many of the larger events described throughout the Feast’s opening ceremony.

In this post, we’ll quote from the Feast opening’s narration (text in red), and elaborate on the larger context of what was going on in the colonies and how the 42nd was involved.

The opening ceremonies begins:

… Here was the southernmost outpost of the French colony of Canada, one of the farthest corners of the Empire. The native peoples were important to the fur trade and important to the rival European powers who wanted to control this rich territory. Fearing British expansion in the Ohio and Wabash country, the French sent a small company of Marines and a blacksmith to establish a post among the Wea. In 1717 these troops brought the pure white flag of the Bourbon rulers to fly over the post they called Ouiatenon.

New France

Since the 17th century, the French played a large role in the fur trade in North America. Closely allied with native tribes – French traders, settlers, and voyageurs traded European goods for beaver pelts.

By the middle of the 18th century, New France stretched from Eastern Canada, through the Great Lakes, into the Great Plains, and down the Mississippi to New Orleans. Many important fortifications in this area were the seeds of major North American cities today. Louisbourg, Québec, Montréal, Ticonderoga, Niagara (Buffalo), Duquesne (Pittsburgh), Detroit, Michillimackinac, Ouiatenon, St. Louis, Chartres, and New Orleans.

Both France and Great Britain set their sights on the Ohio River valley, specifically the Forks of the Ohio (today’s Pittsburgh), which was at both the northwestern edge of Virginia the eastern edge of French Canada. Both Britain and France laid claims to the region and moved in forces – a recipe for conflict.

In 1756, conflict between the British and French erupted into open warfare.

The 42nd Highland Regiment came to America for this French and Indian War in 1756, and fought bravely in a fabled but ultimately unsuccessful attack at Ticonderoga. The 42nd returned to northern New York in 1759, seeing Fort Edward, Ticonderoga again, and Crown Point. In 1760, the regiment participated in the surrender of Montreal.

British Control

Defeated by the British in the “French and Indian War”, France lost almost all her holdings in North America, and this post on the Wabash passed into British hands. Lt. John Butler and a detachment of Roger’s Rangers brought the flag of Great Britain to Ouiatenon.

With the end of hostilities, Britain began to take possession of the fortifications and outposts of Canada. Butler left Detroit on December 10, and arrived at Ouiatenon on January 18, 1761. Butler and his rangers remained until October 25, 1761, when Ensign Holmes of the 80th Foot (Gage’s Light Infantry), and 15 men of the 60th Foot (Royal Americans) relieved the rangers. Near the end of 1761, the Ouiatenon garrison was commanded by Lt. Edward Jenkins, with 20 men of the 60th.

During the period of uncertainty following the French and Indian War, Spain, the third great colonial power in North America, attempted to claim the Great Lakes area [in the hopes that a power vacuum would occur]. Thus the Spanish flag was brought to the Midwest, but the troops never reached Ouiatenon and the post remained under British control.

The 7 years war was more than just North America – as part of the “world” nature of the conflict, the 42nd traveled to the West Indies in 1761, participating in attacks on French (Martinique) and Spanish (Havana) territories.

The British occupation of the posts of the Great Lakes and Wabash was short lived. The Native Peoples resented the British presence and in 1763, the Ottawa Chief Pontiac led an uprising and captured seven forts, including Ouiatenon. Most of the posts were burned, but thanks to the intervention of two French traders, Ouiatenon was spared.

In 1763, many tribes of natives rose up together under Pontiac’s leadership, taking Michillimackinac, Ouiatenon, Miami, St Joseph, Sandusky, Presque Isle, Le Boeuf, and Venango. Niagara was spared from attack, possibly due to its strength. Fort Detroit and Pitt were not so lucky – they fell under siege.

Pontiac’s Rebellion – Enter the 42nd

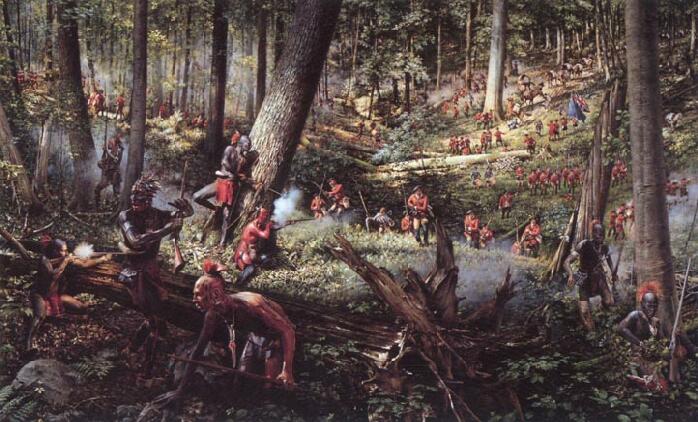

It is here where the stories of Ouiatenon and the 42nd Highlanders come fully together. In July of 1763, the 42nd joined an expedition led by Henry Bouquet to the relief of the besieged Fort Pitt. In August, the expedition was ambushed by Indians in western Pennsylvania at Bushy Run.

The 42nd and 60th successfully relieved Fort Pitt, and strengthened Fort Ligonier, which was also under pressure. The relief of Fort Pitt contributed to the end of the rebellion, and and by 1764 the 42nd was stationed at five outposts in western Pennsylvania.

In October of 1764, Bouquet set out in force into Ohio, and reached peace treaties with the Ohio Indians. Further West, the Illinois frontier was still under French control. The northern district of Louisiana’s seat of control was Fort de Chartres, under the command of St Ange.

The 1763 treaty of Paris gave control of the Illinois to the British, but taking possession of that country was complicated by Pontiac’s rebellion and the disinclination of the Indians to support this “change in management”.

Several different expeditions to take over Fort de Chartres – the seat of government in the Illinois – were planned – some coming up from New Orleans in 1764, only to be persuaded to turn around by attacks from Indians. George Croghan was dispatched from Fort Pitt to Chartres with Alexander Fraser of the 78th Highlanders in 1765 – Fraser reached Chartres but he and his party were in and out of captivity at the hands of the Illinois, before escaping to New Orleans.

George Croghan, Pontiac, and Peace

Croghan’s party, however was attacked at the mouth of the Wabash, and survivors were taken prisoner to Ouiatenon. Croghan was released thanks to Pontiac, and while at Ouiatenon he and Pontiac reached an agreement for peace, as we learn as the opening cermonies continue.

Two years later, in 1765, British Indian agent George Croghan and Pontiac met at Ouiatanon and. negotiated a preliminary treaty which ended the war between the Native Peoples in this region and the British. French traders remained at Ouiatanon but the post was never re-garrisoned by British troops after 1763.

At this point, in August, a detachment of 100 42nd Highlanders, led by Captain Thomas Stirling, was assembled at Fort Pitt for an expedition to relieve the French at Fort de Chartres. The expedition traveled swiftly down the Ohio toward Chartres, and reached the Fort on October 10, 1765.

During the expedition, journals from both Stirling and Lt. Eddington mention Ouiatenon as the expedition passes the mouth of the Wabash. Eddington describes Ouiatenon as having

“vast & extensive plains or Meadows on its banks, abounding with incredible quantities of all kinds of game, and several numerous Tribes of Indians live on its banks: the Piankashaws, part of the Kiquapous & Musqatons, Ouiatanons etc..”

Stirling’s men managed to secure the fort, the French withdrew to the other side of the Mississippi, and the British were able to begin the task of governing the Illinois territory.

American Independence

During the American Revolution, British troops marching to Vincennes paused at Ouiatenon for artillery practice, but it was the victorious Virginians under George Rogers Clark who took possession of the post from the British and for the American forces. Thus the first American flag that could have come to Ouiatenon was the thirteen-striped red and green flag fashioned by Madame Godere at Vincennes.

During the American Revolution, the 42nd fought in many campaigns (primarily in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) quite possibly fighting against many of the same families that it served alongside during the French and Indian War and expeditions into the North American Frontier. To this day, the Black Watch boasts no battle honors on its Regiment’s colors for the 42nd’s part in this war against its own citizens

American Control Comes to the Wabash

… General Anthony Wayne defeated Native forces at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and the flag of Wayne’s Legion became a symbol for friendly native villages. American control had come to the Wabash.

During the Revolution, the 42nd twice encountered Wayne – at the Battle of Paoli, and again at Stony Point.

Fall was a time of homecoming. It was a time for marriages and baptisms and the affairs of church and state.

It was a time of plenty.

A time of happiness.

A time of thanksgiving, and a time of celebration.

It was a time for the Feast of the Hunter’s Moon.

So this fall as you come home to the Feast, celebrate the history of the area, partake in the bounty of food and trade in the Wabash country, be sure and observe the pageantry of the opening ceremonies. While watching the flags raise, and hearing this story told, think of the complementary parts that Fort Ouiatenon and the Scotsmen of our own 42nd Highland Regiment held in the larger story of the formation of America.

And, be sure to enjoy a Forfar Bridie!

Thanks to Kathy Atwell and the Tippecanoe County Historical Association for graciously sharing the opening ceremonies script for this post!